Overview:

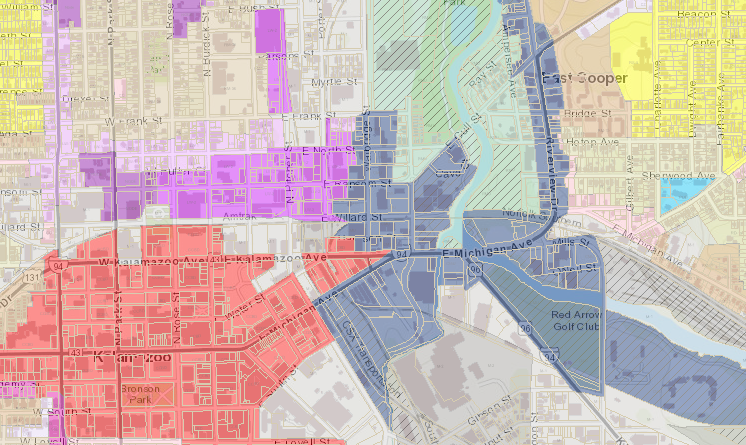

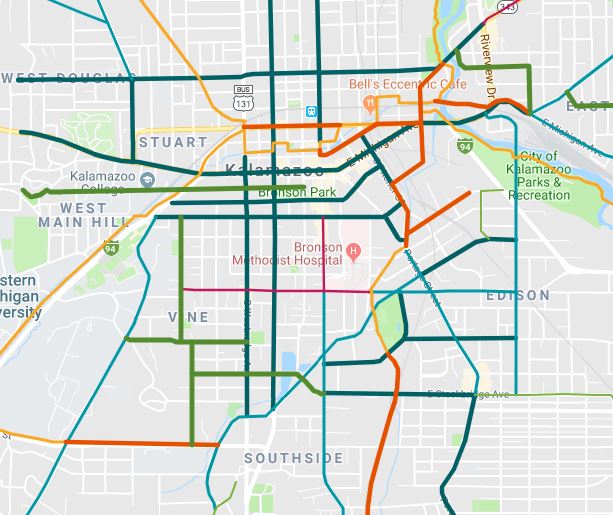

Kalamazoo’s neighborhoods, university campuses, and downtown are currently divided by several wide, high-traffic streets. These streets create barriers for many Kalamazoo residents and visitors – pedestrians, drivers, and bicyclists. The need for changes to the street network is not a new idea. For decades and through many separate planning and outreach efforts the community has been voicing a desire for calmer streets, active and inviting public spaces, and safer travel for all users.

Many of these roadways (Stadium Drive, Kalamazoo Avenue, Michigan Avenue, Park St, Westnedge Avenue, Michikal, and others) were under the jurisdiction of the Michigan Department of Transportation (MDOT), however, in January of 2019, the City of Kalamazoo was transferred control of these streets. Local control of these streets created an opportunity to realize re-designs in the network.

What is the Big Picture?

Since 1965, Downtown Streets have transitioned from two-way to one-way traffic flow with wide, highway-like lanes. Kalamazoo Avenue and Michigan Avenue were once two-way and Michikal did not exist. The long-term goal is to transition many of these streets back to accommodating two-way traffic with improvements to pedestrian safety and addition of bike infrastructure. This would frame Downtown Kalamazoo as a destination rather then a barrier to traffic flow.

Work in 2022 has already started with the Stadium Drive Reconstruction and the awarding of funding for the re-design of Kalamazoo Avenue from one-way operation to two-way operation.

Streets for all Presentation at July 5, 2022 City Commission Meeting

Explore the Story Map to learn about Kalamazoo’s Transportation History

To learn more about the Jurisdictional Transfer and the history of Transportation in Kalamazoo and how the Downtown Network plays a role, check out the Story Map.

Project Managers:

Christina Anderson, City Planner

Anthony Ladd, Assistant Director Public Works

Contractors:

Wightman & Progressive AE - Kalamazoo Avenue Re-Design Contract (Re-Design Kick-off starts in Summer 2022. Project continues into 2024)

MKSK & CDM Smith - Street Design Project & Outreach (2019-2021)

Vision:

To have Downtown streets that meet the needs of the community, promote safe transportation for all, and foster a more vibrant Downtown.

Consistent with Plans:

The Imagine Kalamazoo Master Plan envisions multiple shared goals for the City of Kalamazoo which are centered around Complete Streets and a Transportation network that is safe and effective for all users. The focus is on a Connected City with Complete Neighborhoods and a Vibrant Downtown. The fabric for change is our transportation network.

Connected City, Safe Community, Inviting Public Places, Complete Neighborhoods are all goals addressed by Street Network Re-Design and Implementation efforts.

Adopted in 2019, the Complete Street Policy, alongside the Jurisdictional Transfer process sets the stage for transformation of the street network and is the foundation of the Street Design Manual.

Completed in 2021, the Street Design Manual is the guiding document for the Complete Streets Policy outlining the need for streets for all, designed for safe, reasonable traversal by bicyclists, pedestrians, and motorists. It is a holistic approach.

2017-18 Planning and Environmental Linkages (PEL) Study

Gibbs Planning Group 2017 retail market analysis and 2022 Analysis

Multiple market analyses point to how a change in our street network in the Downtown could have a positive economic impact by creating an environment that is a destination.

Frequently-Asked Questions

This section will be updated periodically.

Why were the streets made one-way in the 1960s?

Answer: When the Michigan Department of State Highways (now MDOT) converted streets in Kalamazoo to one-way operation in October 1965, the primary objective was to make traffic flow faster through the downtown area.

After the conversion, the Michigan Department of State Highways (MDSH) found that average speeds had increased nearly 11 miles per hour during peak volume periods (peak volume is often, but not always, in the morning and afternoon when workers commute from work-to-home or home-to-work), a 56 percent increase over the two-way average.

MDSH also found that the amount of stop delay for vehicles on the one-way streets had, in one case, declined by 75 percent, yet delays on crossing streets (Rose, Burdick, etc.) had increased.

Overall, the conversion to one-way had increased speeds for vehicles traveling through Downtown Kalamazoo. On the other hand, MDSH had expected that crashes might decrease, but “after” studies showed no conclusive evidence supporting the safety aspects of the one-way conversion. In other words, there was no change in the crash picture.

What was the impact of one-way streets?

Answer:

Speed - Increases in traffic speed were an objective of MDSH (now MDOT), which was a normal objective during the 1960s. This type of system has shown to have many negative consequences today, primarily with higher speeds and a greater variation of speed.

Overall in Kalamazoo, nearly 50 percent of all crashes happening in the City are speed-related. That MDOT has promoted high speeds in the City’s Downtown for over a half-century directly contributes to speeding throughout the City. People have been trained to speed through Downtown, so they feel it is appropriate to speed everywhere. Slowing traffic in the Downtown should have a ripple effect throughout the City.

Safety - The wide variation in speed, previously mentioned, is especially troublesome as studies have shown that as the variation in speeds increases, the number of crashes and crash severity, increases.

For example, when we drive on Kalamazoo or Michigan Avenue, we constantly see vehicles traveling 25 to 35 miles per hour along with vehicles traveling 50 to 60 miles per hour mixed in the same traffic flow. This raises the risk for crashes, and many severe crashes on these two streets testify to this phenomenon.

Efficiency – As originally conceived, one-way efficiency is based on the premise that you have a progressive traffic flow down the street.

Progressive traffic flow is when: signals are timed so that a group of vehicles traveling, for example, at 35 miles per hour, can pass through each successive signal without stopping (in short, a free-flow of traffic). However, if cars go 50 or 60 miles per hour mixed with cars going 25 or 35 miles per hour, cars constantly run up on the red lights and destroy progression.

However, the signals along Michigan and Kalamazoo are not progressively timed as you travel along them. To a large extent, this has to do with signal timing and the speed of vehicles not being tied together to allow for traffic to flow progressively.

As mentioned above, the wide variation of individual vehicle speeds is the chief reason for this disparity. The existing street geometry of Kalamazoo and Michigan Avenues (many wide lanes) promotes high speeds, rapid acceleration, and much dodging and weaving (lane-changing) that disrupts the grouping of traffic needed for good progression.

Excessive traffic crashes – In terms of crashes per mile, Michigan and Kalamazoo Avenue segments in the one-way area have consistently ranked in the City's top 25 most dangerous segments over the past ten years. Besides being a crash problem for vehicles, the excessive widths of the streets make timing signals for pedestrian crossing challenging, which contributes to the poor progression on the streets. Where signals do not exist, the safe pedestrian crossing of Kalamazoo and Michigan is problematic not only because of the width of the streets but because of the high variation in vehicle speeds and the extreme amount of lane changing (dodging and weaving), which makes it very difficult for pedestrians to judge oncoming traffic.

Emissions - Besides being a detriment to safety, the wide variance in vehicle speeds and the excessive dodging and weaving of traffic leads to an increase in drivers breaking and acceleration and deceleration of vehicles. This inefficient operation leads to excessive emissions from vehicles, including exhaust gases and material from breaks. It also leads to excessive noise levels, which are well known to compound the negative impact of emissions.

Streets for All Projects Links

Use the following links to visit specific pages dedicated to each project. These project pages will be updated as projects progress.

UPDATES (2019 -2020)